Volume 4 • Issue 4

Common Eyelid Injuries – Part II

by David R. Jordan

M.D., F.A.C.S., F.R.C.S.(C)

INTRODUCTION

Repairing The Lid Margin Following Full Thickness Lacerations

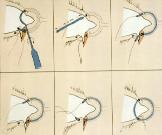

It is essential to reapproximate the lid margin in an accurate and meticulous fashion to avoid notching (Figure 1). A lid notch is not only unsightly, but it disrupts tear exchange and may lead to exposure and tearing. A full-thickness lid margin laceration (Figure 2a) can be repaired either by closing the tarsus first followed by the lid margin, or the lid margin first followed by the tarsus. Landmarks such as the lash line, gray line, or miebomian gland openings are extremely useful to help align the lid margin. If the tarsal plate is closed first we use partial-thickness 5-0 vicryl sutures on a spatula-type needle (s-14). These sutures must not pass full thickness or they may cause corneal epithelial irritation, breakdown, and potential corneal ulceration with infection. The tarsal plate sutures can be temporarily tightened to check lid margin alignment, and the sutures repositioned if necessary to correct any misalignment. The lid margin is then closed. We find that optimal results are obtained when the first stitch in the lid margin is placed through the meibomian gland openings using a 6-0 silk vertical mattress stitch to tent up the edges (Figure 2b). Not only does this help with alignment, but the wound is strong when this suture is closed. This allows for a smooth lid margin to develop once the suture has been removed.

Figure 1– Lid notching of lower lid.

Figure 2a – Full thickness lid laceration involving upper and lower lid margins.

Figure 2b – A vertical mattress suture is used to close the lid margin.

A simple stitch reapproximating the lid margin is often inadequate and may lead to lid notching. A second vertical mattress, and often a third, is placed through the lash line to tent up the edges. Once the lid margin and tarsus have been repaired, the anterior lamella (skin, muscle) is closed. The orbicularis oculi muscle layer does not always need to be closed but when it is, additional strength is added to the wound closure. A 5-0 or 6-0 absorbable chromic or plain suture works well in this layer. Skin is closed with 6-0 silk or nylon in a simple stitch. The lid margin sutures are best left long and tied into the simple skin sutures used to approximate the remaining lid laceration. The 6-0 silk sutures are removed in 12-14 days. In children a 6-0 or 7-0 absorbable suture is generally used to avoid removal (Figure 2c, d).

Figure 2c – Upper and lower lids have been repaired.

Figure 2d – 3 months post-op.

Extensive injuries

With more extensive lid lacerations involving fat herniation and disruption of the levator, it is important to identify the exposed tissue, which is often in an unnatural position (Figure 3). The landmark to orient oneself in the upper and lower lids is the preaponeurotic fat, the orbicularis/skin layer is anterior to this fat, while the levator aponeurosis is immediately posterior to it. The fat should be carefully repositioned. This is often aided by gentle cautery to the fat capsule which allows it to retract into the lid. Only rarely should fat be removed. The levator is gently repositioned and sutured to either the surrounding levator or to the superior edge of tarsus. Lid heights are often hard to determine in the acute post injury eyelid as there may be extensive lid hemorrhage and swelling. An adjustment of the lid height may be required at a later stage. If the tarsus is involved, it is repaired as described earlier. The skin and orbicularis are closed in the usual fashion.

Figure 3 – Full thickness lid laceration with fat exposed (arrow).

The lacrimal gland may occasionally prolapse into the operated field. It often bleeds and must be cauterized, if it does so. It can be resuspended in its fossa using a double-armed 5-0 dacron suture attached to the inside wall of the superior orbital rim.

With more extensive injuries, the globe may be ruptured and should be repaired with the highest priority at all costs (Figure 4). Even if the potential for vision is almost zero, the globe should be repaired initially and then reassessed over the first 7 to 14 days to determine whether enucleation is necessary to avoid sympathetic ophthalmia. This time allows the surgeon to assess the potential for visual recovery and allows the patient time to adjust to the severity of his or her injury and discuss the possible treatment plans,including enucleation. Occasionally, the globe disruption will be too extreme and a primary enucleation will be required.

Figure 4 – Extensive upper and lower lid laceration with globe disruption (arrow).

Canalicular lacerations

Lacerations involving the medial eyelid often disrupt the medial canthal tendon, the upper or lower canaliculus, or both. One should always be suspicious of a canalicular laceration whenever the lid laceration is medial to the pupil (Figure 5a). All canalicular lacerations require repair. There has been some controversy in the past over the role of the superior canaliculus and whether it needs repair if lacerated, but several investigators have now proven its importance in tear drainage. It must be repaired just as much as the lower canaliculus, and hopefully the myth that it doesn’t require repair will be soon be abolished.

Figure 5a – Laceration medial to the pupil (arrow) involves the canalicular system.

A variety of techniques can be used to repair a canalicular laceration. Three essential principles must be followed: the canalicular ends must be accurately approximated with a fine suture under direct visualization (re-establishing patency), a stent is required to support the canaliculus while healing, and, the technique must be atraumatic to the canalicular system. At present, silicone tubing (0.025 inches outside diameter x 0.012 inches inside diameter) is the most effective stent, because it is soft, flexible, and readily supports the canalicular walls. This canalicular repair technique is best carried out by an individual having a thorough knowledge of the anatomy of the area (Figure 5b).

Figure 5b – Canalicular repair technique using the pigtail probe.

Canthal tendon injuries

With more extensive medial canthal tendon injuries and avulsions, accurate realignment of the tendon and bone may be required. Surgical correction must reposition the medial canthal tendon so that it is on the same horizontal plane as the tendon on the contralateral side. In addition, the tendon has to be placed posteriorly enough, so that the medial eyelid hugs the globe, otherwise a space will be left between the lid and the globe medially. It is important to reapproximate and repair the canaliculi with stents if needed. If the medial canthal tendon is avulsed, the tendon can be directly resutured to the periosteum, providing some is present. If there are multiple nasal fractures, a transnasal wire procedure may be required. Alternatively, if the bones are intact and stable, a Peton screw or micro plate can be used to anchor the medial canthal tendon into the frontal process of the maxilla.

Lacerations involving the lateral canthal tendon area are more straightforward because there are no canaliculi. If one or both of the lids have been lacerated laterally, it is important to reattach the canthal tendon itself or the lateral tarsus to the periosteum on the inside wall of the lateral orbital rim to achieve the proper lateral canthal approximation. If no periosteum is available, a small hole can be drilled through the lateral rim to act as an anchor site. The lateral tarsal strip procedure can be extremely useful here. If additional tissue is required, this can be mobilized from the lateral lid, periosteum, or temporal skin area.

SUMMARY

Damage to the eyelid, medial canthus, and lateral canthus may result from blunt, penetrating or avulsive injuries. Because the force and velocity of the injury can be significant, one should always be suspicious of underlying injury to the globe, orbital structures, paranasal sinuses, and bony wall. The fundamental principles involved in repairing lid and adnexal lacerations include identification of the structures involved and reapproximation of the normal tissue anatomy. If the laceration is medial to the pupil, a canalicular laceration is likely (all canalicular lacerations require repair). When tissue is lost, additional reconstructive techniques are required to replace the missing structure. A thorough knowledge of the eyelid anatomy is essential when repairing eyelid lacerations.

If you have any questions regarding the topics of this newsletter, or requests for future topics of InSight, please contact Dr. David R. Jordan office by telephone at (613) 563-3800.