Volume 7 • Issue 3

Common Orbital Disorders in Adults

by David R. Jordan

M.D., F.A.C.S., F.R.C.S.(C)

INTRODUCTION

Orbital disorders although uncommon generally present with proptosis and/or a shift in globe position (horizontally or vertically). Inflammation may or may not be present. The disease process may have originated in the orbit, extend from an adjacent sinus, the intracranial area, or eyelids. It may also represent a manifestation of a systemic disease. When an orbital disorder is suspected, a simple systematic method of evaluation should be employed to identify the process. The important questions to answer include: Where is the disease located? How has the disease developed (temporal sequence)? and How has the process affected the orbital structures?

The temporal sequence of development (when did it start, how fast did it develop, is it intermittent or gradually progressive) as well as the functional disruption (effect on motility, vision, globe shift) are extremely helpful in developing a differential diagnosis.

Five basic processes can occur either independently or together within and around the orbit: inflammation, neoplasia, structural abnormalities (congenital or acquired), vascular lesions and degenerations and depositions.1 These processes are not mutually exclusive and may occur in concert but for the most part one process is the dominant underlying pathophysiology of presentation. Based on over 1400 adult orbital cases the breakdown into these categories are as follows:1

- Inflammation (cellulitis, Grave’s, pseudotumor): 57%

- Neoplasia (lymphoma, secondary metastatic tumors, lacrimal gland tumors): 10.2%

- Structural abnormalities (dermoids, epidermoids, mucoceles): 15.8%

- Vascular lesions (hemangiomas, lymphangiomas, varices, cartoid cavernous sinus fistulas): 2.8%

- Degenerations and depositions (orbital fat prolapse, amyloid): 1.7%

Certain orbital lesions may occasionally not require therapy, however, most necessitate some form of treatment, that may include antibiotics, steroids, radiation, chemotherapy and/or surgery.

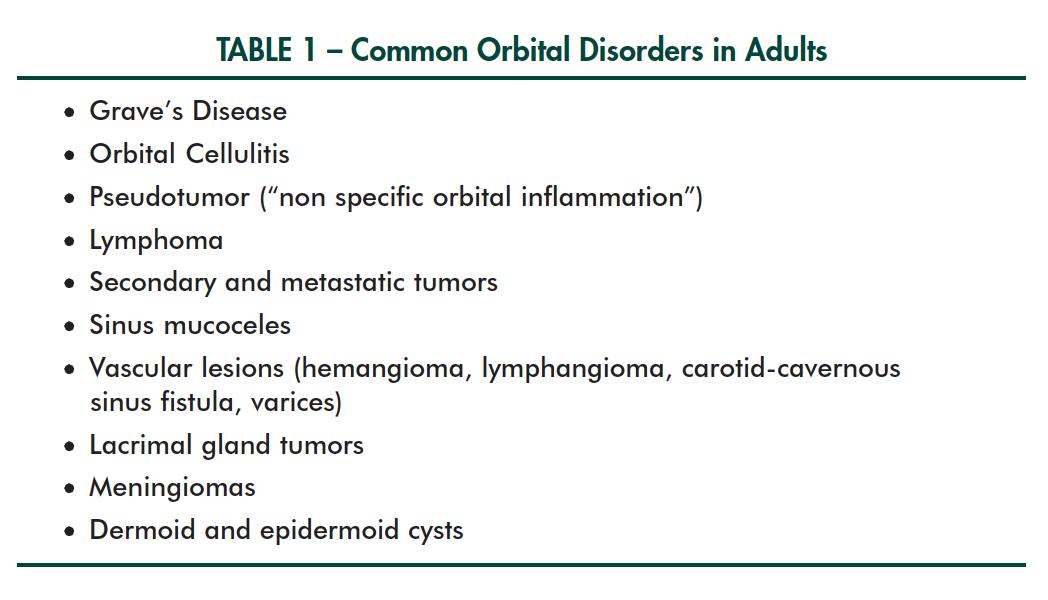

A list of common orbital problems in adults is seen in Table 1.

Grave’s Disease

Grave’s Disease (Figure 1) may present acutely over several days to weeks or more gradually over weeks to months. Not all patients have all the classic signs. Not all patients will be hyperthyroid, some may be euthyroid or hypothyroid. Some patients will have unilateral disease, others will have bilateral disease. It is extremely variable. In those with acute inflammatory signs the patients may have rapid heart rate, sweating, hot/cold intolerance, proptosis, lid retraction, conjunctival chemosis, etc. An acute onset unilateral Grave’s Disease can mimic an orbital cellulitis and orbital pseudotumor at times and should be kept in mind in the differential diagnosis of acute inflammation.

Figure 1 – Proptosis, upper and lower lid retraction give rise to the classic thyroid stare.

Orbital Celluliti

Orbital cellulitis (Figure 2) is the model for acute inflammation. It is characterized by rapid development (days) of inflammatory signs (warmth, injection, swelling, malaise and loss of function). There is a rapid onset of pain, injection, swelling and proptosis that if left untreated may lead to potential damage to the orbital and ocular structures. The majority of orbital cellulitis is due to a spill over from a sinus infection (especially in children), but it may also be secondary to an ocular cause (endophthalmitis), systemic bacteremia or due to a secondary infection of a nearby skin wound. Organisms responsible vary widely and may include staphylococcus aureus, streptococcus species or a mixture of aerobic and anaerobic organisms. Cultures of the blood, nasopharynx, and conjunctiva are important to try and identify the organism so that appropriate antibiotics can be started. CT scanning documents the extent of orbital involvement and may show opacified sinuses. Once the diagnosis is made, treatment is carried out on a prompt to urgent basis depending upon the severity of the disease process. Broad spectrum antibiotics (ex. cloxacillin and clindamycin) or the latest generation of cephalosporin are a good initial treatment until a specific bug is identified.

Figure 2 – Proptosis with upper and lower eyelid swelling in orbital cellulitis.

Orbital Pseudotumor

Pseudotumor(Figure 3a) or more specifically “nonspecific orbital inflammation” refers to an inflammatory process within the orbit that has no clear etiology. It can present very acutely (days) and mimic an orbital cellulitis at times with orbital and periorbital redness and swelling along with proptosis and restricted orbital motility. It may also come on more slowly over weeks. Generally, the patients are not as sick feeling as orbital cellulitis patients and do not have a fever. Computerized tomography documents the orbital structures involved and characteristically reveals normal sinuses. Nonspecific orbital inflammation (pseudotumor) may involve the muscles (myositis), the lacrimal gland (dacryoadenitis) or can occur throughout the orbital tissue (diffuse, apical, anterior). If the disease process involves only one or two extra-ocular muscles that are well visualized on CT scanning, the diagnosis is clear (myositis) and the patients can be started on oral prednisone. However, if the process is located in the lacrimal gland or orbital tissue itself, a biopsy is needed first (prior to initiating steroids) to confirm the diagnosis.

Figure 3a –Ptosis, proptosis and globe shift inferiorly due to a Pseudotumor in the superior orbit.

Lymphoma

Lymphomas (Figure 3b) are one of the common orbital neoplasms affecting the orbit. The orbit or conjunctiva may be the initial site of presentation of the disease. They may initially be noticed as a salmon pink mass within the conjunctival fornix. Alternatively, patients may present with proptosis and no conjunctival signs. CT scanning demonstrates a relatively well defined multi-lobulated growth. Bone destruction is characteristically absent. The lymphomatous process may involve one or both orbits. Biopsy is essential to establish the diagnosis. The patients are then evaluated for systemic involvement (even if the disease is in the conjunctiva). If the process is confined to the orbit, radiation is beneficial, if there is systemic involvement –chemotherapy is required.

Figure 3b – Bilateral lacrimal gland masses (arrows) due to lymphoma.

Secondary and metastatic tumors

Orbital tumors may be benign or malignant, primary or secondary. They generally present with proptosis, globe displacement ± loss of motility. There are rarely any signs of inflammation and generally they come on over several weeks to months. They may display infiltrative or noninfiltrative features. Clinically, the benign masses are usually noninfiltrative and associated and with mass effect without destruction or entrapment. In contrast, malignant masses are usually infiltrative and associated with evidence of functional damage and/or entrapment along with destruction of surrounding bone.

Secondary and metastatic tumors (Figure 4a) appear to be increasing in frequency, reflecting a change in natural history and prolonged longevity of cancer patients treated with modern modalities. Their presentation varies from rapidly developing masses, often with adjacent tissue infiltration, bone destruction, to slow cicatrization of soft tissue. The characteristic clinical features of most metastatic disease is their unrestricted growth which leads to local infiltrates and entrapment of structures. Breast carcinoma is the most common orbital metastasis in most series of orbital tumors, and thus a female predominance is noted (Figure 4b). Lung cancer is more common in men, as are gastrointestinal cancers and kidney tumors. Sometimes the primary remains unknown.

Figure 4a – Left globe shifted inferiorly secondary to metastatic renal cell carcinoma to left orbit.

Figure 4b – Patient with past history of breast cancer presents with a mass in right superior orbit (arrows), along orbital rim.

A specific list of all the various orbital tumors is tremendously long. For the most part orbital tumors have a similar presentation (i.e. proptosis, globe shift ± loss of function). CT scanning is essential in characterizing their location and biopsy generally defines the pathology which helps to determine a treatment plan.

Mucoceles

Mucoceles often develop following a traumatic insult to the orbital bones and sinuses years earlier. The sinus outflow is blocked and overtime a cystic process (mucocele) develops in the sinus. Proptosis, globe displacement and a past history of trauma are the clues to diagnosis (Figure 5). Mucoceles take years to develop. As a result, they lead to a very slowly developing shift in the globe. CT scanning confirms the diagnosis. Surgical removal of the mucocele with re-establishment of the sinus drainage is the appropriate treatment.

Figure 5 – Right globe shifted downward and outward due to a frontal ethmoidal mucocele.

Vascular Lesions (hemangioma, lymphangioma, cartoid cavernous sinus fistula)

There are a variety of vascular lesions that may involve the orbit. Their patterns of presentation often depend on the blood flow within. They may have a high, low or no f low. Their onset may be intermittent, slowly progressive, or catastrophically rapid (as in carotid cavernous sinus fistula).

Cavernous hemangiomas (very low flow) are the most common benign orbital tumor. They develop very slowly over years and the patient may not even be aware they are present. Proptosis is a common clinical sign and characteristically there are few, if any complaints, and no sign of inflammation. CT scanning demonstrates a discrete well-defined tumor within the muscle cone. If the tumor is gradually enlarging they can be surgically removed.

Other examples in the vascular category include an orbital varix (low f low) which generally causes intermittent proptosis. Proptosis while bending over, or during a Valsalva maneuver is characteristic. CT scanning generally illustrates a multi-lobulated process within the orbital tissues. The intermittent nature of the globe dis-placement is characteristic.

Cartoid-cavernous sinus fistulas often have a sudden onset (mins-hours) of severe proptosis, loss of vision, injection, and severe limitation of extra-ocular motility (Figure 6). They truly are an orbital emergency. Urgent angiography is required with emobolization of the fistula. Unfortunately, vision is usually lost, by the time they reach the hospital.

Figure 6 – Sudden proptosis, vascular injection, visual loss and motility restriction in a patient with a cartoid cavernous sinus fistula.

Lacrimal gland tumors

The lacrimal gland may be involved with an infective or inflammatory process (dacryoadenitis), neoplastic process (tumor) or a structural problem (lacrimal cyst). The two major groups of neoplasms involving the lacrimal gland are epithelial and lymphoproliferative lesions. Lymphomatous tumors generally develop slowly over several months in an older age group (60+). The lacrimal gland is enlarged clinically and shifts the eye down and in (Figure 3b). Diagnosis is made on biopsy.

The intrinsic epithelial lacrimal gland tumors can be benign or malignant. “The Benign Mixed Lacrimal Gland Tumor” (pleomorphic adenoma) may present from childhood to the eighth decade as a slow growing tumor causing a slow, non-painful displacement of the globe downward and inward along with proptosis. There are no sensor y defects, loss of function or bone destruction on CT scanning.

The malignant intrinsic lacrimal gland tumors (ex. Adenoid cystic carcinomas, malignant mixed tumor) may present anywhere from the teenage years to the eighth decade and often develop more rapidly over weeks to months. There may be sensory defects, loss of function and bony destruction associated with their development. These tumors are infiltrative, aggressive and associated with a high mortality rate.

Meningiomas

Meningiomas occur more frequently in women and generally present between the third and sixth decade.1 They may arise and extend into the orbit from the intracranial cavity, arise from the optic nerve sheath or rarely arise from the orbital soft tissues. They are usually slowly growing neoplasms that declare themselves clinically by compression or encasement (or both) of normal anatomic structures.

Meningiomas frequently lead to visual loss; those confined to and arising from the optic nerve sheath cause unilateral deterioration whereas those arising intracranially often ultimately affect vision bilaterally. The more confined the space and the closer to the optic nerve they arise, the earlier their effect on vision. Thus, even small tumors of the optic canal cause early visual disturbances whereas those involving the sphenoid wing may lead to structural displacement and disfigurement first, with functional deficits appearing later. The most useful investigative tests are CT scanning and MRI scanning.

Dermoid and Epidermoid cysts

Dermoids and epidermoids are a result of surface ectoderm being pinched off and buried beneath the skin. They may present years later as a soft mobile or non-mobile, well-defined cystic structure along or within the orbit.

Summary

Orbital diseases, may come on catastrophically (minutes to hours), acutely (days), subacutely (weeks) or on a more chronic and gradual basis (months). Although a tumor is what most patients are concerned about, almost 60% of orbital diseases are inflammatory in nature (cellulitis, pseudotumor, Grave’s) and have favorable outcome.

References

1. Rootman J. Pathophysiologic Patterns of Orbital Disease, Anatomic Patterns of Orbital Disease, Pathophysiologic Approach to Clinical Analysis of Orbital Disease, Investigation of Orbital Disease and its Effect on Function. Chapters 4,5,6,7, pages 51-117. In Diseases of the Orbit, J.B. Lippincott Co, Philadelphia.

If you have any questions regarding the topics of this newsletter, or requests for future topics of InSight, please contact Dr. David R. Jordan office by telephone at (613) 563-3800.