Volume 11 • Issue 3

Ophthalmic Management of Facial Nerve Paralysis

Part I: Anatomy and common causes of the problem

by David R. Jordan

M.D., F.A.C.S., F.R.C.S.(C)

INTRODUCTION

Paralysis of the facial nerve is a common neurological problem with potentially severe ophthalmic consequences. It may also be devastating to ones self-esteem, particularly in cases that extend for a long period and where residual deformities or aberrant regeneration are significant. There is often little appreciation for the physical discomfort, difficulty and frustration patients may go through when they struggle to do seemingly simple things that are often taken for granted. General problems associated with facial paralysis include: muscle weakness causing a droopy appearance (eyebrow, lower eyelid, midface, mouth) (Figure 1a) rhinorhea, nasal stuffiness, difficulty speaking, difficulty eating/drinking, sensitivity to sound, excess or reduced salivation, facial swelling, diminished or distorted taste, pain in the ear, drooling.

Figure 1a – drooping eyebrow, retracted ectropic lower lid, drooping mid face, due to a right seventh nerve palsy

Eye related problems (dryness, irritation, sensitivity) are a direct result of orbicularis weakness causing a poor or absent blink, and inability to completely close the eyelids (lagopthalmos) (Figure 1b). There may be lack of tears (decreased production) or excess tearing (corneal exposure with reflex tearing, loss of lid tone and lacrimal pump mechanism or crocodile tears due to aberrant regeneration). Anterior segment examination may reveal conjunctival injection, punctuate corneal erosions, and cornel ulceration due to the exposure. Corneal perforation is possible in severe cases. The eyebrow commonly droops downward with the upper eyelid skin, and the lower lid is often retracted inferiorly or ectropic.

Figure 1b – severe lagopthalmos due to loss of orbicularis muscle function

Anatomy

The origin of a seventh nerve problem may be anywhere from the cerebral cortex to the peripheral branches of the facial nerve. A brief review of the facial nerve anatomy and etiology of facial nerve paralysis is important to consider as it may benefit the medical and/or surgical treatment of the patient.

The facial nerve has two roots: a larger motor root that supplies the frontalis and orbicularis muscles as well as the buccinator, platysma, stapedius, stylohyoid muscles and the posterior belly of the digastric muscles: and a smaller sensory root, the nervus intermedius, that carries special sensory fibers for taste from the anterior tongue and general sensory fibers from the external auditory meatus, soft palate, and adjacent pharynx; it also carries parasympathetic secretomotor fibers to the submaxillary, sublingual, and lacrimal glands. (Figure 2a).

Figure 2a – topographic anatomy of the facial nerve

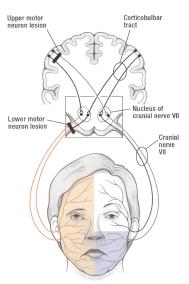

The “facial motor area” in the brain is located in the precentral gyrus of the frontal lobe. Neurons from this area travel in the corticobulbar tract through the upper mid brain to the lower brainstem where they synpase in the facial nerve nucleus located in the pons (Figure 2a). The corticobulbar tracts for the upper face cross and recross in reaching the facial nerve nucleus. The tracts to the lower face are crossed only once (Figure 2b).

Figure 2b – distribution of facial muscles paralysed after a supranuclear lesion of the corticobulbar tract and after a lower motor neuron lesion of the facial nerve.

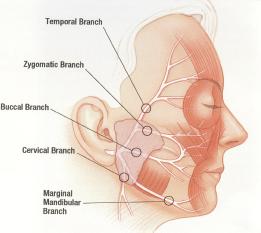

Motor axons from the seventh nerve nucleus then exit dorsally and loop around the nearby abducens nucleus (cranial nerve VI) heading toward the cerebellopontine angle where they exit (Figure 2a). Just prior to emerging from the brainstem, sensory and parasympathetic fibers (tearing, salivation, taste) combine to form a small bundle, the nervus intermedius. This emerges, along with the motor root, and lies between the motor root and the acoustic nerve (cranial nerve VIII). At the cerebellopontine angle, these nerves may come in close contact with the anterior inferior cerebellar artery, which may lie either dorsal or ventral to them. This relationship appears to play a role in the etiology of hemifacial spasm. The facial nerve, nervus intermedius and acoustic nerve enter the temporal bone through the internal auditory canal. The facial nerve and nervus intermedius then leave the acoustic nerve to enter the fallopian canal (or facial canal) in the temporal bone where it courses serpiginously for approximately 30 mm through the labyrinthine and mas-toid segments of the temporal bone. The motor and sensory roots temporarily fuse within the facial canal and become thickened by the presence of the geniculate ganglion. The first sensory branch to leave the facial nerve is the greater superficial petrosal nerve (carries parasympathetic fibers, sympathetic and sensory fibers). It exits within the facial canal (laryrinthine segment), synapses within the sphenopalatine ganglion and then joins the lacrimal nerve within the orbit to supply parasympathetic secretomotor fibers to the lacrimal gland. It also carries symapathetic nerve fibers from the lacrimal gland and some sensory fibers from the pharyngeal and nasal mucosa. A small motor branch exits the seventh nerve (mastoid segment) and travels to the stapedius of the inner ear. The chorda tympani is the terminal sensory branch of the nervus intermedius and usually arises from the distal third of the mastoid segment of the facial nerve. The chorda tympani nerve contains parasympathetic secretomotor fibers to the submandibular and sublingual salivary glands. It also carries taste fibers from the anterior two thirds of the tongue and some sensory fibers from the posterior wall of the external auditory meatus (pain and temperature). The facial nerve exits the temporal bone at the stylomastoid foramen to become a peripheral nerve. It immediately enters the parotid gland and divides into the temporal, zygomatic, buccal, mandibular and cervical branches (Figure 2c). Branching patterns vary among individuals and the numerous interconnections among the branches correlate with the clinical picture seen with aberrant regeneration following facial nerve paralysis.

Figure 2c – branching pattern of the seventh facial nerve in upper and lower face.

Causes of Facial Nerve Palsy

Supranuclear lesions affecting the corticopontine nerve pathways prior to the facial nerve nucleus result in paralysis of the opposite lower facial muscles with sparing of the up-per face (e.g. stroke patients). Lesions in the pons adjacent to the 7th nerve nuclei usually produce complete ipsilateral facial paralysis but may also affect the nearby 6th nerve nuclei (abducens) giving rise to a conjugate gaze palsy and inter-nuclear ophthalmoplegia. (e.g. multiple sclerosis). Diseases affecting the seventh nerve after it exits from the brainstem (peripheral facial nerve paralysis) produce complete ipsilateral facial paralysis. Peripheral facial nerve paralysis may be a diagnostic challenge at times. Although idiopathic paralysis of the facial nerve or “Bell’s palsy” is the most common cause of a peripheral facial nerve paralysis there are many other causes that may be treatable. The medical history (e.g. facial nerve paralysis, +/– hearing loss, +/– double vision, +/– pain, +/– facial numbness, +/– vesicles, +/– rash), onset and duration of the facial paralysis are very important in determining the etiology. A past history of facial skin cancer, previous head and neck cancer or other cancer, recent immunization, etc. may also provide useful clues to the diagnosis.

Bell’s Palsy – is an idiopathic disorder characterized by acute facial paralysis of the lower motor neuron that is not associated with other neurologic findings. It accounts for almost 75% of all acute facial nerve palsies, with the highest incidence in the 15–45 year old age group. The annual incidence is approximately 1 in 5000 with pregnant females and diabetics more predisposed. Increasing evidence points to latent herpes viruses (herpes simplex type 1 and herpes zoster), which are reactivated from cranial nerve ganglia (e.g. the geniculate ganglia), as the primary cause of Bells Palsy. Inflammation and edema of the facial nerve within the facial canal initially results in a reversible neuropraxia but ultimately degeneration ensues. The palsy is often sudden in onset and evolves rapidly with maximal facial weakness developing within 2 days. Associated symptoms may include decreased production of tears, hyperacusis and altered taste. Patients may also have otalgia, facial or retroauricular pain, which is typically mild and may precede the palsy. Overall, Bell’s palsy has a fair prognosis without treatment, with almost 75% of patients recovering normal function. Major improvement occurs in most within 3 weeks. If recovery does not occur within this time it is unlikely to be seen until 4 to 6 months when nerve regrowth and reinnervation have occurred. There is good evidence that prednisone administered in the first seven days and ideally within 72 hours (and continued for about a week) will shorten the course and severity of Bell’s palsy in 10-20% of patients. Treatment with antivirals seems logical in Bell’s palsy because of the probable involvement of herpes viruses and recent studies have found that patients treated with a combination of an antiviral (acyclovir) and prednisone have a better outcome than those with prednisone alone.

Ramsay Hunt Syndrome – is similar to Bell’s palsy how-ever the varicella zoster virus (rather than herpes simplex virus) involving the geniculate ganglion is responsible for the paralysis. Severe pain (within the ear) and a vesicular eruption within the external auditory meatus +/– the tympanic membrane are characteristic. The pain may start prior to the paralysis while the vesicles may appear prior to, concurrent with or after the onset of the facial paralysis. There may also be vertigo (dizziness) and hearing loss due to involvement of the vestibuloacoustic nerve. Prednisone and an antiviral medication (acyclovir, famciclovir) are also beneficial in treatment of Ramsey Hunt syndrome and ideally should be started within 72 hours of the blisters appearance.

Differentiating Bells Palsy from Ramsay Hunt Syndrome:

1) Pain: Bells Palsy patients may complain of pain (often in or behind ear) which can be acute. However it will tend to fade within a week or two. The pain associated with Ramsey Hunt Syndrome is more severe and more likely to be felt inside the ear. It may start before muscle weakness is apparent and last for weeks or months.

2) Vertigo: Dizziness is occasion-ally reported in Bells Palsy patients but often associated with Ramsey Hunt Syndrome. It can be more severe and longer lasting.

3) Hearing Loss: Unlike Bells Palsy, Ramsey Hunt can also affect the auditory nerve resulting in hearing deficit. This should not occur with Bells Palsy and is an important clue to the diagnosing physician.

4) Vesicles: The primary symptom that makes a diagnosis of Ramsey Hunt Syndrome is the appearance of blisters in the ear. They can appear prior to, concurrent to or after the onset of facial paralysis. They can be expected to last 2-5 weeks and can be quite painful. The pain may continue after the blisters have disappeared. Blisters are often the only clear visible sign that identifies Ramsey Hunt. Unfortunately, they may not be evident during the diagnostic exam. They can be present but too deep within the ear to be seen. Or they can be too small to be seen. At times they do not appear in the ear at all, but may be present in the mouth or throat. It is also possible for the virus to reactivate without blisters (Zoster sine herpete). “Zoster sine herpete” is thought to be the cause of almost a third of facial palsies previously diagnosed as idiopathic.

5) Swollen and tender lymph nodes near the affected areas – While Bells Palsy is not contagious, Zoster blisters are infectious. Contact with an open blister by someone who has never had chicken pox can result in transmission of the virus. The result will be chicken pox, not shingles or facial paralysis.

Expanding lesions in the cerebellopontine angle – the seventh nerve (and nervus intermedius) are in intimate con-tact with the acoustic nerve in this region and expanding lesions (acoustic neuromas, menigiomas, dermoid cysts, or aneurysms) frequently produce facial paralysis associated with ipsilateral hearing loss, tinnitus, +/– dizziness/unsteadiness (acoustic nerve). The roots of the fifth, ninth and tenth cranial nerves lie nearby and also may become involved. Acoustic neuromas or acoustic schwanomas are derived from schwan cells and account for about 7% of all intracranial tumors. Hearing loss and tinnitus are early symptoms followed by dizziness. As the tumor grows larger it projects from the internal auditory meatus into the cerebellopontine angle and begins to compress the cerebellum, brainstem and other cranial nerves (5 and 7). Hearing loss and tinnitus are early symptoms followed by dizziness and unsteadiness.

Compression of the facial nerve within the facial canal – may occur with sarcoidosis, leukemic infiltrates or schwanomas (neurilemomas or neuromas). Facial nerve paralysis is the most common neurological manifestation of sarcoidosis and it may be unilateral or bilateral. Sarcoidosis may also affect branches of the seventh nerve within the parotid gland or within the subarachnoid space. Schwanomas (neurilemomas or neuromas) are the most common neoplasm of the facial nerve. The slow progressive onset of facial nerve paralysis from this tumor contrasts to the acute onset of paralysis in Bell’s Palsy.

Trauma to the facial nerve – can occur with fractures to the temporal bone or the mandible or during surgery to the mandible. The temporal branches of the facial nerve are particularly vulnerable to trauma over the zygomatic arch and over the temple, superolateral to the brow.

Acute otitis media. mastoiditis – in children or adults may lead to facial nerve paralysis as a result of the nearby inflammatory process.

Metastatic lesions – a history of cancer (breast, lung, thyroid, kidney, ovary or prostate) associated with a rapidly progressive facial nerve paralysis strongly suggests a metastatic lesion and should be investigated (CT, MRI).

Facial Skin cancer – “squamous cell carcinoma” has a ten-dency to track along nerves – any history of facial skin cancer in the distribution of the seventh nerve may be a clue to the cause of the seventh nerve paralysis.

Malignancies of the parotid gland – may also affect the facial nerve; a palpable or visible mass in the vicinity of this gland is apparent on exam.

Postinfectious polyneuritis (Guillain-Barre syndrome) – is a presumed hypersensitivity or autoimmune response leading to demyelination, edema, and compression of nerve roots within their dural sheaths, resulting in weakness and paresthesias. Cranial nerve involvement is seen in half of all cases. The facial nerve is the most frequently affected and often bilaterally.

Hemifacial spasm – is characterized by an uncontrollable, unilateral contraction of the facial muscles as a result of a vascular compression of the facial nerve root in the cerebellopontine angle. The vessel irritates the seventh nerve and as a result it spontaneously fires leading to contraction of the facial muscles on one half of the face. Most commonly, the offending vessel is the anterior inferior cerebellar artery, which travels adjacent to the seventh nerve, nervus intermedius and acoustic nerves. With time the vascular compression can lead to weakness of the facial muscles, thus not only are there episodic spasms of the facial muscles but between spasms the facial muscle tone is weak on the affected side. Essential blepharospasm on the other hand involves uncontrollable, bilateral facial muscle spasms. An unknown defect in the basal ganglia is the suspected etiology. The seventh nerve root is not involved at the cerebellopontine angle as in hemifacial spasm and seventh nerve weakness does not occur with this entity.

Immunization for polio or influenza – has been associated with facial nerve weakness.

Lyme disease – may cause unilateral or bilateral facial nerve paralysis. The disease is characterized by a rash (erythema chronicum migrans – multiple expanding ring lesions with central clearing), fever, headache, enlarged lymph nodes, myalgia, cardiac conduction defects and arthritis.

Other more uncommon causes of a seventh nerve paralysis – HIV, infectious mononucleosis, chickenpox, mumps, influenza, polio, leprosy, tuberculosis, syphilis, tetanus, diptheria, myasthenia gravis, botulism, acute porphyria, Melkerson – Rosenthal Syndrome, diabetes, Lupus.

If you have any questions regarding the topics of this newsletter, or requests for future topics of InSight, please contact Dr. David R. Jordan office by telephone at (613) 563-3800.