Volume 2 • Issue 3

Tearing in Adults

by David R. Jordan

M.D., F.A.C.S., F.R.C.S.(C)

INTRODUCTION

The lacrimal gland, located under the upper eyelid along and posterior to the lateral orbital rim is responsible for the production of tears. The gland produces a baseline amount of tears to moisten the cornea and will also respond to emotion or eye irritation by producing larger quantities of tears.

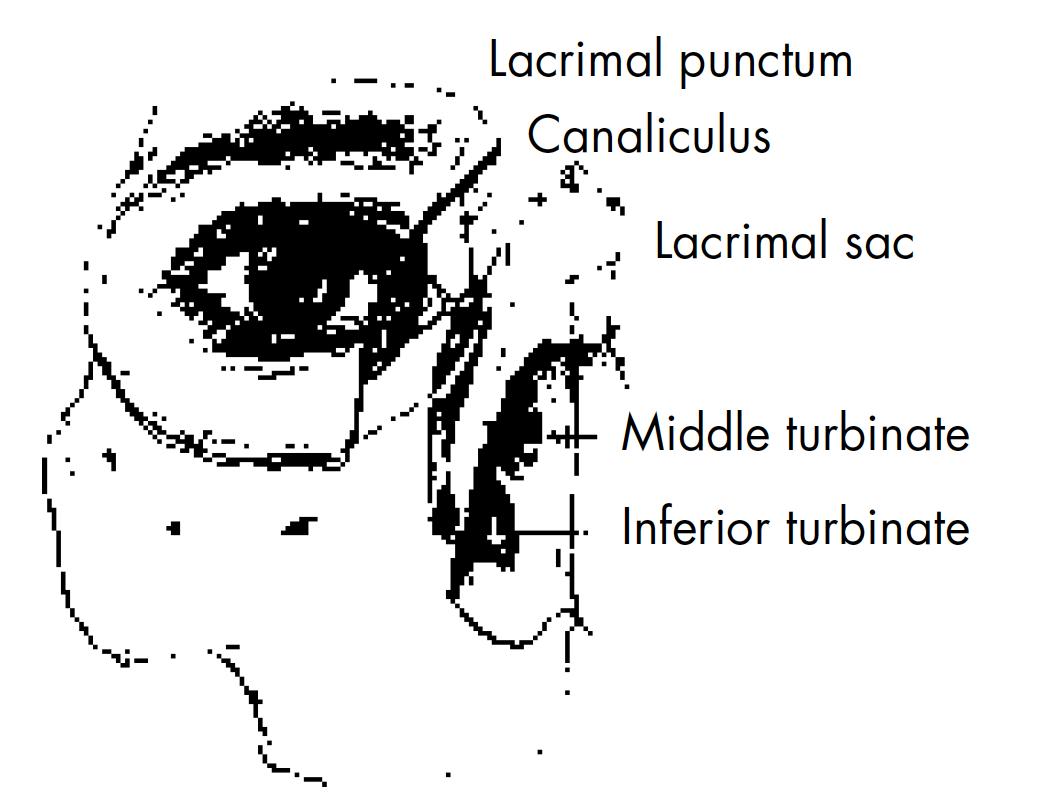

The nasolacrimal system is located medially and responsible for tear drainage. Each eyelid has a punctal opening and canaliculus which drains tears into the nasolacrimal sac and then into the nose [Fig. 1].

Figure 1 – Nasolacrimal system anatomy.

Tears may well up in the eye because too many tears are produced or because the tears are not being drained properly. Excess tears from any cause give the eye a moist appearance. Increased tear accumulation can also cause difficulty with reading. Tears continually running onto the cheek are annoying and may cause skin irritation from the regular wiping that results.

What causes excess tearing in adults?

Injury, birth defects, narrowing of the nasolacrimal system associated with age, eyelid malpositions, and infection, especially of the lacrimal sac, can lead to improper tear drainage at the punctum, canaliculus, lacrimal sac or nasolacrimal duct and lead to a back-up of tears which then overflow on to the face.

Eye infections, inturned eyelashes, exposure to the wind, yawning, glaucoma, certain drugs, eye strain or even Dry Eyes can also cause excessive tearing, by an increase in the amount of tears produced.

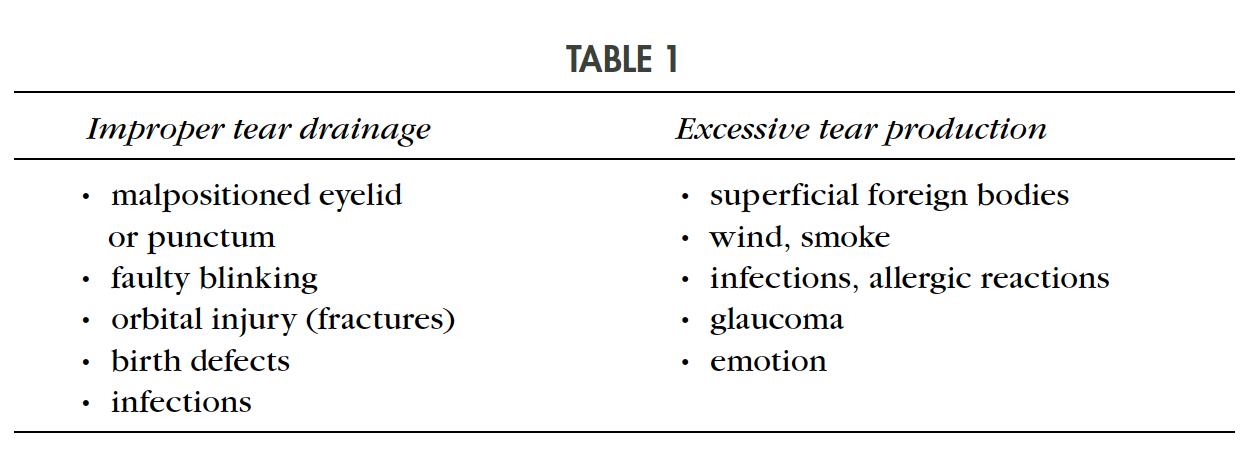

When a patient presents with tearing, it is important to determine whether there is excess tear production or improper tear drainage (Table 1).

How does one determine a cause for the tearing?

The eyelids need to be in normal position and have a good tone in order for the tears to be exchanged over the cornea and pumped into the tear canal.

Excessive tearing does not always mean an excess of tear production or blockage of the drainage system. Patients with a dry eye, not uncommonly, present to the office complaining of tearing. When the amount of baseline lubricating tears secreted is too low to maintain necessary moisture for the eye, the lacrimal gland reacts by producing additional tears. The nasolacrimal system may not be able to handle this out pouring of additional tears which then leads to episodes of tears overflowing onto the face, even though the underlying problem is too few baseline tears. This is often referred to as “reflex tearing”. The patient may complain of burning eyes or dry, sandy eyes which is a tip off to the diagnosis. If they do not volunteer this information by history, they should always be asked about symptoms of dry eyes.

Sometimes there are obvious clues to the diagnosis of a tearing problem as one interviews the patient. Examples include, facial nerve paralysis, traumatic scars involving the lids, ectropion, entropion, excoriation of the lid skin (dermatitis), congenital developmental eyelid anomalies. Each of these conditions can either upset the normal blinking rate and lead to tearing or cause eye irritation which leads to an increase production of tears which “overflow” onto the face, e.g. lashes rubbing on the cornea in entropion.

Infection in the nasolacrimal sac (“Dacryocystitis”) is usually obvious and presents with redness, swelling, pain and discharge [Fig. 2].

Figure 2 – Dacryocystitis illustrated.

If there are no clues on history or eyelid examination, various tear studies are required. A Schirmer study measures the amount of baseline tear production and is a good test for detecting dry eyes. A dye disappearance test is useful to determine the physiologic patency of the nasolacrimal system. In this test, a drop of 2% fluorescein dye is placed into the conjunctival fornix and observed. It should disappear by 5 minutes. If it does not, there is some degree of holdup in the outflow tract. Irrigation of the nasolacrimal system can also be done to see if there is complete blockage or whether the system is simply narrow. Dacryocystography is a diagnostic test requiring injection of dye into the nasolacrimal system followed by an x-ray. This allows examination of the anatomy of the lacrimal system to determine if there is a stone [Fig. 3] or other obstruction causing the excessive tearing. Lacrimal scintillography involves placing a radionucleotide labelled eye drop into the conjunctival fornix, followed by a measurement of the rate at which it disappears into the rest of the system.

Figure 3 – Example of a nasolacrimal sac stone.

Very occasionally, the exact cause cannot be determined. In such cases, the patient may have to learn to live with the tearing problem.

How is excessive tearing treated?

Treatment depends on the problem. If the patient is felt to have dry eyes, a trial of artificial tears is recommended. If this does not help, the punctal openings can be blocked with small plugs to allow more retention of tears. If tearing is secondary to irritation by an inturned lash, the lash is removed. This can be done manually at first. If the lash recurs, it can be ablated with cryotherapy, electrolysis or with laser. Abnormalities of the eyelid (entropion, ectropion) require simple reconstructive procedures done under local anesthesia. For facial paralysis, a tarsorrhaphy may be required.

If the nasolacrimal duct is severely narrowed or completely blocked, surgery to open it is required (Dacryocystorhinostomy). This procedure is done under local stand-by anesthesia (intravenous narcotic and anxiolytics). The nasolacrimal sac and surrounding tissues are frozen with local anaesthesia (2% xylocaine with epinephrine). The nasal passage is also frozen with medication such as cocaine which also leads to vasoconstriction of the tissues. During surgery, the nasolacrimal sac is opened and anostomosed to the nasal mucosa. A silicone tube is then placed in the nasolacrimal system and left for 6 to 10 months to maintain the passageway [Fig. 4]. Removal of the tube is carried out in the office simply by cutting the tube and letting it fall out.

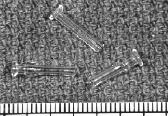

Very occasionally, the nasolacrimal sac is totally scarred shut and cannot be opened. In these instances, a small pyrex glass tube (Jones tube) is put in place to drain tears from the eye into the nose [Fig. 5]. The tubes are generally well tolerated and serve as a conduit for tear passage. They occasionally need rinsing to keep them open and occasionally need to be exchanged, each of which are minor office adjustments.

What complications can occur with tear duct surgery?

95-97% of the Dacryocystorhinostomy surgeries work fine and the tearing resolves, whereas 3-5% will not work and the patient remains with a tearing problem. Complications postoperatively are generally of a minor nature. Swelling around the incision, and eyelids, maybe present postoperatively and settles with ice packs. The incision for this surgery sits at the junction of the nose and eyelid and blends into the surrounding tissue nicely. By 3 months, it is almost invisible in over 95% of patients. As with any surgical procedure, there is the possibility of infection but it is very uncommon.

Figure 4 – Example of a nasolacrimal sac stone.

Figure 5 – Jones tube illustrated.

Bleeding from the nose or surgical site occasionally occurs to a minor degree on the day of surgery and it is common to develop a black eye after this procedure. Continued and heavy bleeding resistant to manual compression of the nose is uncommon and may require a return to the hospital with placement of a nasal pack for 24 to 48 hours. The silicone tubes may cause some minor eye irritation for 1 to 2 weeks. They are very well tolerated for the 6 to 12 months that they are in place but occasionally may lead to a smell in the nose which, if persistent, will lead to early removal.

Occasionally the new tear duct passageway will scar shut (3-5% of cases). If this occurs, simply re-placing the tubes back into the passage for an additional 6 months may be all that is needed to re-open the system. At other times, a revision of the procedure may be suggested.

If you have any questions regarding the topics of this newsletter, or requests for future topics of InSight, please contact Dr. David R. Jordan office by telephone at (613) 563-3800.